The Parser's Hidden Assumptions

[Written by Claude with my help. I did find these problems, but with Claude's help doing the code searches and debugging.]

After months of architecture design and infrastructure building, I finally got to implement an actual story. Not just any story, but one of the classics: Roger Firth's "Cloak of Darkness." It's the "Hello World" of interactive fiction—simple enough to implement quickly, complex enough to expose fundamental issues.

And expose issues it did.

The Story That Broke the Parser

Cloak of Darkness has a deceptively simple puzzle: hang your cloak on a hook. The command seems straightforward: `HANG CLOAK ON HOOK`. But when I typed this into my freshly-minted Sharpee platform, the parser choked.

What I discovered sent me down a rabbit hole that would fundamentally change how I think about parser design.

Debugging with Platform Events

My first instinct was to add comprehensive debugging. I implemented a platform event system—separate from game events—that would let me trace exactly what the parser was doing:

[parser.tokenize_complete] input="hang cloak on hook" tokens=4

[parser.noun_phrase_start] tokens=[{word: "cloak", partOfSpeech: [NOUN]}, {word: "on", partOfSpeech: [UNKNOWN]}, {word: "hook", partOfSpeech: [NOUN]}]

[parser.parse_success] pattern=VERB_NOUN directObject="cloak on hook"Wait. The parser thought "cloak on hook" was a single noun phrase? That's when it hit me: prepositions weren't registered in the vocabulary system. The parser literally didn't know "on" was a preposition.

The Vocabulary Gap

Digging deeper, I found that while `lang-en-us` dutifully defined all the English prepositions, the vocabulary registration system had no way to use them. We registered verbs, directions, and special words, but prepositions? They were orphaned data.

This wasn't just a bug—it was a fundamental design flaw. The parser was trying to match patterns like `VERB_NOUN_PREP_NOUN` without understanding what a preposition was.

From Bug to Architecture

At this point, I could have just added `registerPrepositions()` and called it a day. But the more I looked at the parser, the more hardcoded assumptions I found:

- Fixed pattern matching with no extensibility

- No way for stories to define custom grammar

- Hardcoded confidence scores

- No pattern priorities

The parser wasn't parsing—it was pattern matching with a very limited set of patterns.

The Grammar Rules Engine

That's when I decided to pivot from a quick fix to a proper solution: a grammar rules engine. Instead of hardcoded patterns, we'd have a declarative system that feels natural to JavaScript developers:

grammar

.define('put :item in|into|inside :container')

.where('item', { portable: true })

.where('container', { kind: 'container', open: true })

.mapsTo('putting');

grammar

.define('hang :garment on :hook')

.where('garment', { wearable: true })

.where('hook', { kind: 'supporter' })

.mapsTo('putting')

.withPriority(150); // Higher than generic 'put'This builder pattern is familiar from Express routing and other JS libraries. The `:slot` syntax makes it clear what's a variable versus literal text. And it compiles down to entity IDs for the stdlib layer.

Scope: The Next Frontier

But grammar is only half the parsing equation. The other half is scope—determining which objects are available for interaction. The current system only understands "what's in your location," but interactive fiction needs more:

- Seeing a bulldozer from an observatory's telescope

- Hearing noises through walls

- Magic items that make distant objects accessible

So we designed a scope rule system that's both powerful and stdlib-oriented:

scopeRules.add({

id: 'observatory_view',

fromLocations: ['observatory'],

includeEntities: ['bulldozer', 'mountain'],

forActions: ['examining', 'looking'],

message: 'You can see it from here with the telescope.'

});Language-Specific, Not Language-Locked

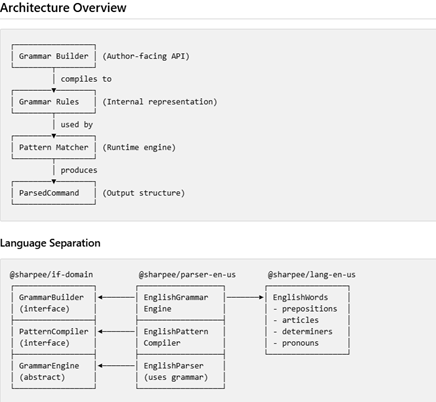

Throughout this redesign, I've been careful to maintain the language separation. The grammar engine interfaces live in `if-domain`, but the English-specific implementation lives in `parser-en-us`. The pattern syntax, word order rules, and vocabulary all come from the language-specific packages.

This means when someone wants to implement a Spanish parser, they can use the same grammar engine with different patterns:

// English: subject-verb-object

grammar.define('give :item to :recipient')

// Spanish: more flexible word order

grammar.define('dar :item a :recipient')

grammar.define('a :recipient dar :item')The Road Ahead

What started as a simple bug fix—making "hang cloak on hook" work—has evolved into a comprehensive parser redesign. But that's the thing about building an IF platform: every simple feature reveals layers of complexity.

The new grammar engine will take an hour or two to implement, but it's the right foundation. It turns the parser from a pattern matcher into a true language processor, one that stories can extend and customize.

Sometimes the best bugs are the ones that force you to stop and think: is this really a bug, or is it telling me something about my design?

In this case, that cloak hanging on its hook was pointing the way to a better architecture.

Next up: Implementing the grammar engine and finally getting that cloak where it belongs.